How Do Animals Help Humans With Emotional Support

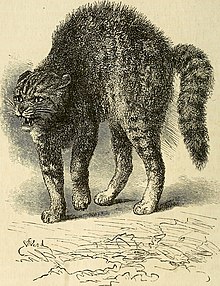

A drawing of a cat by T. W. Wood in Charles Darwin'due south book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, described as acting "in an affectionate frame of mind".

Emotion is defined equally whatsoever mental feel with loftier intensity and high hedonic content.[ane] The existence and nature of emotions in animals are believed to exist correlated with those of humans and to have evolved from the same mechanisms. Charles Darwin was one of the first scientists to write virtually the subject, and his observational (and sometimes anecdotal) approach has since adult into a more robust, hypothesis-driven, scientific approach.[2] [iii] [4] [five] Cognitive bias tests and learned helplessness models have shown feelings of optimism and cynicism in a wide range of species, including rats, dogs, cats, rhesus macaques, sheep, chicks, starlings, pigs, and honeybees.[6] [7] [8] Jaak Panksepp played a large role in the written report of animate being emotion, basing his inquiry on the neurological aspect. Mentioning seven core emotional feelings reflected through a variety of neuro-dynamic limbic emotional action systems, including seeking, fearfulness, rage, lust, care, panic and play.[nine] Through brain stimulation and pharmacological challenges, such emotional responses can be effectively monitored.[9]

Emotion has been observed and further researched through multiple different approaches including that of behaviourism, comparative, anecdotal, specifically Darwin'due south approach and what is most widely used today the scientific arroyo which has a number of subfields including functional, mechanistic, cognitive bias tests, cocky-medicating, spindle neurons, vocalizations and neurology.

While emotions in animals is nevertheless quite a controversial topic, it has been studied in an extensive array of species both large and pocket-size including primates, rodents, elephants, horses, birds, dogs, cats, honeybees and crayfish.

Etymology, definitions, and differentiation [edit]

The word "emotion" dates back to 1579, when information technology was adapted from the French discussion émouvoir, which means "to stir up". However, the earliest precursors of the word likely date back to the very origins of language.[10]

Emotions have been described as discrete and consistent responses to internal or external events which take a particular significance for the organism. Emotions are brief in duration and consist of a coordinated prepare of responses, which may include physiological, behavioural, and neural mechanisms.[11] Emotions have also been described as the result of development because they provided good solutions to aboriginal and recurring bug that faced ancestors.[12]

Laterality [edit]

Information technology has been proposed that negative, withdrawal-associated emotions are processed predominantly by the right hemisphere, whereas the left hemisphere is largely responsible for processing positive, approach-related emotions. This has been chosen the "laterality-valence hypothesis".[xiii]

Bones and circuitous human being emotions [edit]

In humans, a distinction is sometimes made betwixt "basic" and "complex" emotions. 6 emotions take been classified as basic: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise.[14] Complex emotions would include contempt, jealousy and sympathy. However, this distinction is hard to maintain, and animals are often said to limited even the complex emotions.[15]

Background [edit]

Behaviourist approach [edit]

Prior to the development of animate being sciences such as comparative psychology and ethology, interpretation of animal behaviour tended to favour a minimalistic approach known as behaviourism. This arroyo refuses to accredit to an creature a capability beyond the least demanding that would explain a behaviour; anything more than this is seen as unwarranted anthropomorphism. The behaviourist argument is, why should humans postulate consciousness and all its near-man implications in animals to explain some behaviour, if mere stimulus-response is a sufficient explanation to produce the same furnishings?

Some behaviourists, such as John B. Watson, claim that stimulus–response models provide a sufficient caption for animal behaviours that have been described every bit emotional, and that all behaviour, no affair how complex, can be reduced to a simple stimulus-response association.[sixteen] Watson described that the purpose of psychology was "to predict, given the stimulus, what reaction will take place; or given the reaction, state what the situation or stimulus is that has caused the reaction".[sixteen]

The cautious wording of Dixon exemplifies this viewpoint:[17]

Recent work in the expanse of ideals and animals suggests that it is philosophically legitimate to ascribe emotions to animals. Furthermore, it is sometimes argued that emotionality is a morally relevant psychological country shared by humans and not-humans. What is missing from the philosophical literature that makes reference to emotions in animals is an effort to analyze and defend some particular business relationship of the nature of emotion, and the function that emotions play in a label of human nature. I debate in this newspaper that some analyses of emotion are more apparent than others. Because this is so, the thesis that humans and nonhumans share emotions may well be a more difficult case to make than has been recognized thus far.

Moussaieff Masson and McCarthy describe a like view (with which they disagree):[xviii]

While the study of emotion is a respectable field, those who piece of work in it are usually academic psychologists who confine their studies to man emotions. The standard reference work, The Oxford Companion to Animate being Behaviour, advises creature behaviourists that "Ane is well advised to report the behaviour, rather than attempting to get at whatever underlying emotion. There is considerable doubtfulness and difficulty related to the interpretation and ambiguity of emotion: an animal may brand sure movements and sounds, and show certain brain and chemical signals when its body is damaged in a item mode. But does this mean an beast feels—is aware of—hurting as we are, or does it simply hateful it is programmed to deed a certain way with certain stimuli? Similar questions can be asked of whatsoever activity an animal (including a human being) might undertake, in principle. Many scientists regard all emotion and cognition (in humans and animals) as having a purely mechanistic basis.

Because of the philosophical questions of consciousness and mind that are involved, many scientists have stayed away from examining beast and human emotion, and have instead studied measurable brain functions through neuroscience.

Comparative arroyo [edit]

In 1903, C. Lloyd Morgan published Morgan'south Catechism, a specialised form of Occam's razor used in ethology, in which he stated:[19] [xx]

In no case is an brute action to be interpreted in terms of higher psychological processes,

if it can be adequately interpreted in terms of processes which stand lower in the scale of psychological development and development.

Darwin'southward approach [edit]

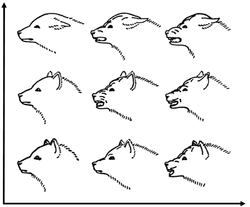

Charles Darwin initially planned to include a affiliate on emotion in The Descent of Man only as his ideas progressed they expanded into a volume, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.[21] Darwin proposed that emotions are adaptive and serve a communicative and motivational role, and he stated three principles that are useful in understanding emotional expression: First, The Principle of Serviceable Habits takes a Lamarckian opinion by suggesting that emotional expressions that are useful will be passed on to the offspring. 2nd, The Principle of Antithesis suggests that some expressions exist merely because they oppose an expression that is useful. Third, The Principle of the Direct Activity of the Excited Nervous System on the Body suggests that emotional expression occurs when nervous energy has passed a threshold and needs to be released.[21]

Darwin saw emotional expression as an outward communication of an inner country, and the form of that expression often carries beyond its original adaptive use. For instance, Darwin remarks that humans often present their canine teeth when sneering in rage, and he suggests that this ways that a human ancestor probably utilized their teeth in aggressive activity.[22] A domestic dog's simple tail wag may exist used in subtly different ways to convey many meanings as illustrated in Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Human being and Animals published in 1872.

- Examples of tail position indicating unlike emotions in dogs

-

"Pocket-size dog watching a true cat on a table"

-

"Domestic dog approaching another domestic dog with hostile intentions"

-

"Dog in a humble and affectionate frame of listen"

-

"Half-bred shepherd dog"

-

"Canis familiaris caressing his master"

Anecdotal arroyo [edit]

Evidence for emotions in animals has been primarily anecdotal, from individuals who interact with pets or captive animals on a regular basis. Even so, critics of animals having emotions frequently advise that anthropomorphism is a motivating factor in the interpretation of the observed behaviours. Much of the argue is acquired by the difficulty in defining emotions and the cognitive requirements idea necessary for animals to feel emotions in a like way to humans.[15] The trouble is fabricated more than problematic by the difficulties in testing for emotions in animals. What is known most human emotion is near all related or in relation to human advice.

Scientific approach [edit]

In recent years, the scientific customs has become increasingly supportive of the thought of emotions in animals. Scientific research has provided insight into similarities of physiological changes between humans and animals when experiencing emotion.[23]

Much support for animal emotion and its expression results from the notion that feeling emotions doesn't crave significant cognitive processes,[fifteen] rather, they could be motivated by the processes to act in an adaptive way, every bit suggested by Darwin. Recent attempts in studying emotions in animals take led to new constructions in experimental and information gathering. Professor Marian Dawkins suggested that emotions could exist studied on a functional or a mechanistic basis. Dawkins suggests that only mechanistic or functional research will provide the reply on its own, but suggests that a mixture of the two would yield the about pregnant results.

Functional [edit]

Functional approaches rely on understanding what roles emotions play in humans and examining that role in animals. A widely used framework for viewing emotions in a functional context is that described past Oatley and Jenkins[24] who encounter emotions as having three stages: (i) appraisement in which there is a witting or unconscious evaluation of an issue as relevant to a particular goal. An emotion is positive when that goal is avant-garde and negative when it is impeded (ii) action readiness where the emotion gives priority to one or a few kinds of action and may requite urgency to one and then that it can interrupt or compete with others and (3) physiological changes, facial expression so behavioural action. The structure, however, may exist too wide and could be used to include all the animate being kingdom as well every bit some plants.[15]

Mechanistic [edit]

The second approach, mechanistic, requires an examination of the mechanisms that drive emotions and search for similarities in animals.

The mechanistic arroyo is utilized extensively by Paul, Harding and Mendl. Recognizing the difficulty in studying emotion in non-verbal animals, Paul et al. demonstrate possible ways to meliorate examine this. Observing the mechanisms that role in human emotion expression, Paul et al. suggest that concentration on similar mechanisms in animals can provide clear insights into the animal experience. They noted that in humans, cognitive biases vary co-ordinate to emotional land and suggested this as a possible starting point to examine animal emotion. They propose that researchers may be able to use controlled stimuli which accept a particular meaning to trained animals to induce particular emotions in these animals and appraise which types of basic emotions animals tin experience.[25]

Cognitive bias test [edit]

Is the glass one-half empty or half full?

A cognitive bias is a pattern of difference in judgment, whereby inferences near other animals and situations may exist drawn in an illogical way.[26] Individuals create their own "subjective social reality" from their perception of the input.[27] Information technology refers to the question "Is the glass half empty or one-half full?", used as an indicator of optimism or pessimism. To test this in animals, an private is trained to anticipate that stimulus A, e.g. a twenty Hz tone, precedes a positive upshot, e.yard. highly desired food is delivered when a lever is pressed by the animal. The same individual is trained to anticipate that stimulus B, due east.chiliad. a 10 Hz tone, precedes a negative event, e.g. bland food is delivered when the animal presses a lever. The creature is then tested by beingness played an intermediate stimulus C, e.g. a xv Hz tone, and observing whether the animal presses the lever associated with the positive or negative advantage, thereby indicating whether the animal is in a positive or negative mood. This might be influenced by, for example, the type of housing the fauna is kept in.[28]

Using this approach, it has been institute that rats which are subjected to either handling or tickling showed unlike responses to the intermediate stimulus: rats exposed to tickling were more optimistic.[6] The authors stated that they had demonstrated "for the get-go time a link betwixt the direct measured positive affective country and conclusion making under incertitude in an animal model".

Cognitive biases have been shown in a wide range of species including rats, dogs, rhesus macaques, sheep, chicks, starlings and honeybees.[half-dozen]

Self-medication with psychoactive drugs [edit]

Humans tin can take a range of emotional or mood disorders such as depression, anxiety, fearfulness and panic.[29] To treat these disorders, scientists have developed a range of psychoactive drugs such as anxiolytics. Many of these drugs are developed and tested by using a range of laboratory species. It is inconsistent to argue that these drugs are effective in treating human emotions whilst denying the feel of these emotions in the laboratory animals on which they have been developed and tested.

Standard laboratory cages prevent mice from performing several natural behaviours for which they are highly motivated. As a consequence, laboratory mice sometimes develop abnormal behaviours indicative of emotional disorders such every bit depression and anxiety. To ameliorate welfare, these cages are sometimes enriched with items such as nesting material, shelters and running wheels. Sherwin and Ollson[xxx] tested whether such enrichment influenced the consumption of Midazolam, a drug widely used to treat anxiety in humans. Mice in standard cages, standard cages but with unpredictable husbandry, or enriched cages, were given a pick of drinking either not-drugged water or a solution of the Midazolam. Mice in the standard and unpredictable cages drank a greater proportion of the anxiolytic solution than mice from enriched cages, indicating that mice from the standard and unpredictable laboratory caging may have been experiencing greater anxiety than mice from the enriched cages.

Spindle neurons [edit]

Spindle neurons are specialised cells found in iii very restricted regions of the human brain – the anterior cingulate cortex, the frontoinsular cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.[31] The first 2 of these areas regulate emotional functions such as empathy, speech, intuition, rapid "gut reactions" and social organization in humans.[32] Spindle neurons are also found in the brains of humpback whales, fin whales, killer whales, sperm whales,[32] [33] bottlenose dolphin, Risso's dolphin, beluga whales,[34] and the African and Asian elephants.[35]

Whales have spindle cells in greater numbers and are maintained for twice as long equally humans.[32] The exact function of spindle cells in whale brains is still not understood, but Hof and Van Der Gucht believe that they act equally some sort of "high-speed connections that fast-rail information to and from other parts of the cortex".[32] They compared them to express trains that bypass unnecessary connections, enabling organisms to instantly procedure and act on emotional cues during complex social interactions. Nevertheless, Hof and Van Der Gucht clarify that they practise not know the nature of such feelings in these animals and that we cannot just apply what we see in great apes or ourselves to whales. They believe that more than work is needed to know whether emotions are the same for humans and whales.

Vocalizations [edit]

Though non-human animals cannot provide useful verbal feedback nearly the experiential and cognitive details of their feelings, various emotional vocalizations of other animals may exist indicators of potential affective states.[ix] First with Darwin and his research, it has been known that chimpanzees and other bully apes perform laugh-like vocalizations, providing scientists with more symbolic self-reports of their emotional experiences.[1]

Inquiry with rats has revealed that under particular atmospheric condition, they emit 50-kHz ultrasonic vocalisations (USV) which have been postulated to reverberate a positive affective state (emotion) analogous to primitive human joy; these calls have been termed "laughter".[36] [37] The 50 kHz USVs in rats are uniquely elevated by hedonic stimuli—such equally tickling, rewarding electrical brain stimulation, amphetamine injections, mating, play, and aggression—and are suppressed past aversive stimuli.[six] Of all manipulations that elicit 50 kHz chirps in rats, tickling by humans elicits the highest rate of these calls.[38]

Some vocalizations of domestic cats, such as purring, are well known to be produced in situations of positive valence, such as mother kitten interactions, contacts with familiar partner, or during tactile stimulation with inanimate objects every bit when rolling and rubbing. Therefore, purring tin can be mostly considered equally an indicator of "pleasure" in cats.[39]

Low pitched bleating in sheep has been associated with some positive-valence situations, as they are produced by males as an estrus female is approaching or by lactating mothers while licking and nursing their lambs.[39]

Neurological [edit]

Neuroscientific studies based on the instinctual, emotional action tendencies of non-human animals accompanied by the brains neurochemical and electrical changes are deemed to all-time monitor relative main process emotional/affective states.[nine] Predictions based on the research conducted on animals is what leads analysis of the neural infrastructure relevant in humans. Psycho-neuro-ethological triangulation with both humans and animals allows for further experimentation into animal emotions. Utilizing specific animals that showroom indicators of emotional states to decode underlying neural systems aids in the discovery of critical encephalon variables that regulate animate being emotional expressions. Comparing the results of the animals converse experiments occur predicting the affective changes that should outcome in humans.[9] Specific studies where at that place is an increase or subtract of playfulness or separation distress vocalizations in animals, comparing humans that exhibit the predicted increases or decreases in feelings of joy or sadness, the weight of show constructs a concrete neural hypothesis concerning the nature of touch on supporting all relevant species.[9]

Criticism [edit]

The statement that animals experience emotions is sometimes rejected due to a lack of college quality bear witness, and those who do not believe in the idea of animal intelligence oftentimes argue that anthropomorphism plays a role in individuals' perspectives. Those who reject that animals have the capacity to experience emotion practice so mainly by referring to inconsistencies in studies that take endorsed the conventionalities emotions exist. Having no linguistic means to communicate emotion beyond behavioral response interpretation, the difficulty of providing an account of emotion in animals relies heavily on interpretive experimentation, that relies on results from human being subjects.[25]

Some people oppose the concept of animal emotions and suggest that emotions are not universal, including in humans. If emotions are not universal, this indicates that there is not a phylogenetic relationship between homo and non-homo emotion. The relationship drawn by proponents of brute emotion, then, would be merely a suggestion of mechanistic features that promote adaptivity, merely lack the complexity of human emotional constructs. Thus, a social life-style may play a office in the process of basic emotions developing into more complex emotions.

Darwin concluded, through a survey, that humans share universal emotive expressions and suggested that animals likely share in these to some caste. Social constructionists disregard the concept that emotions are universal. Others concord an intermediate stance, suggesting that bones emotional expressions and emotion are universal but the intricacies are developed culturally. A written report by Elfenbein and Ambady indicated that individuals within a particular culture are better at recognising other cultural members' emotions.[40]

Examples [edit]

Primates [edit]

Primates, in detail great apes, are candidates for being able to experience empathy and theory of mind. Great apes accept complex social systems; young apes and their mothers have strong bonds of attachment and when a baby chimpanzee[41] or gorilla[42] dies, the mother volition commonly carry the body around for several days. Jane Goodall has described chimpanzees as exhibiting mournful behavior.[43] Koko, a gorilla trained to utilize sign linguistic communication, was reported to have expressed vocalizations indicating sadness after the death of her pet cat, All Ball.[44]

Across such anecdotal evidence, back up for empathetic reactions has come up from experimental studies of rhesus macaques. Macaques refused to pull a chain that delivered food to themselves if doing so also caused a companion to receive an electrical daze.[45] [46] This inhibition of hurting another conspecific was more pronounced between familiar than unfamiliar macaques, a finding like to that of empathy in humans.

Furthermore, there has been research on alleviation behavior in chimpanzees. De Waal and Aureli establish that third-party contacts attempt to relieve the distress of contact participants past consoling (e.m. making contact, embracing, grooming) recipients of aggression, especially those that have experienced more intense aggression.[47] Researchers were unable to replicate these results using the same observation protocol in studies of monkeys, demonstrating a possible deviation in empathy between apes and other monkeys.[48]

Other studies accept examined emotional processing in the great apes.[49] Specifically, chimpanzees were shown video clips of emotionally charged scenes, such every bit a detested veterinary procedure or a favorite food, then were required to lucifer these scenes with one of two species-specific facial expressions: "happy" (a play-face) or "sad" (a teeth-baring expression seen in frustration or after defeat). The chimpanzees correctly matched the clips to the facial expressions that shared their meaning, demonstrating that they understand the emotional significance of their facial expressions. Measures of peripheral skin temperature also indicated that the video clips emotionally affected the chimpanzees.

Rodents [edit]

In 1998, Jaak Panksepp proposed that all mammalian species are equipped with brains capable of generating emotional experiences.[50] Subsequent piece of work examined studies on rodents to provide foundational back up for this claim.[51] One of these studies examined whether rats would piece of work to alleviate the distress of a conspecific.[52] Rats were trained to press a lever to avoid the delivery of an electric shock, signaled past a visual cue, to a conspecific. They were so tested in a state of affairs in which either a conspecific or a Styrofoam block was hoisted into the air and could be lowered past pressing a lever. Rats that had previous feel with conspecific distress demonstrated greater than 10-fold more than responses to lower a distressed conspecific compared to rats in the control group, while those who had never experienced conspecific distress expressed greater than 3-fold more responses to lower a distressed conspecific relative to the control group. This suggests that rats will actively work to reduce the distress of a conspecific, a miracle related to empathy. Comparable results accept also been found in similar experiments designed for monkeys.[53]

Langford et al. examined empathy in rodents using an approach based in neuroscience.[54] They reported that (ane) if two mice experienced hurting together, they expressed greater levels of hurting-related behavior than if hurting was experienced individually, (2) if experiencing different levels of pain together, the behavior of each mouse was modulated by the level of pain experienced by its social partner, and (iii) sensitivity to a baneful stimulus was experienced to the same caste by the mouse observing a conspecific in hurting as it was past the mouse directly experiencing the painful stimulus. The authors suggest this responsiveness to the pain of others demonstrated by mice is indicative of emotional contamination, a phenomenon associated with empathy, which has also been reported in pigs.[55] 1 behaviour associated with fearfulness in rats is freezing. If female rats experience electric shocks to the feet and then witness another rat experiencing similar footshocks, they freeze more females without any experience of the shocks. This suggests empathy in experienced rats witnessing some other individual being shocked. Furthermore, the demonstrator'south behaviour was changed by the behaviour of the witness; demonstrators froze more following footshocks if their witness froze more creating an empathy loop.[56]

Several studies take also shown rodents can respond to a conditioned stimulus that has been associated with the distress of a conspecific, as if information technology were paired with the direct experience of an unconditioned stimulus.[57] [58] [59] [threescore] [61] These studies propose that rodents are capable of shared affect, a concept critical to empathy.

Horses [edit]

Although not directly prove that horses experience emotions, a 2016 study showed that domestic horses react differently to seeing photographs of positive (happy) or negative (angry) man facial expressions. When viewing angry faces, horses look more than with their left middle which is associated with perceiving negative stimuli. Their heart rate likewise increases more quickly and they testify more stress-related behaviours. 1 rider wrote, 'Experienced riders and trainers can learn to read the subtle moods of individual horses according to wisdom passed downwardly from 1 horseman to the adjacent, but also from years of trial-and-mistake. I suffered many bruised toes and nipped fingers before I could detect a curious swivel of the ears, irritated picture of the tail, or concerned cockle above a long-lashed centre.' This suggests that horses have emotions and display them physically but is non concrete evidence.[62]

Birds [edit]

Marc Bekoff reported accounts of animal behaviour which he believed was evidence of animals being able to experience emotions in his book The Emotional Lives of Animals.[63] The post-obit is an extract from his book:

A few years ago my friend Rod and I were riding our bicycles effectually Boulder, Colorado, when nosotros witnessed a very interesting encounter amid five magpies. Magpies are corvids, a very intelligent family of birds. 1 magpie had obviously been hit by a car and was laying dead on the side of the road. The 4 other magpies were standing effectually him. One approached the corpse, gently pecked at it-simply equally an elephant noses the carcass of some other elephant- and stepped back. Another magpie did the same matter. Next, one of the magpies flew off, brought back some grass, and laid it by the corpse. Another magpie did the same. So, all four magpies stood vigil for a few seconds and ane by ane flew off.

Bystander amalgamation is believed to represent an expression of empathy in which the bystander tries to console a disharmonize victim and alleviate their distress. There is bear witness for bystander affiliation in ravens (due east.g. contact sitting, preening, or beak-to-nib or beak-to-torso touching) and also for solicited bystander affiliation, in which in that location is post-conflict affiliation from the victim to the eyewitness. This indicates that ravens may be sensitive to the emotions of others, however, relationship value plays an of import role in the prevalence and function of these post-disharmonize interactions.[64]

The chapters of domestic hens to experience empathy has been studied. Mother hens testify 1 of the essential underpinning attributes of empathy: the ability to be affected by, and share, the emotional land of their distressed chicks.[65] [66] [67] Withal, evidence for empathy between familiar adult hens has non yet been institute.[68]

Dogs [edit]

Some enquiry indicates that domestic dogs may experience negative emotions in a similar manner to humans, including the equivalent of sure chronic and acute psychological conditions. Much of this is from studies by Martin Seligman on the theory of learned helplessness every bit an extension of his involvement in low:

A dog that had earlier been repeatedly conditioned to associate an aural stimulus with inescapable electric shocks did not subsequently try to escape the electric shocks after the warning was presented, even though all the dog would have had to practice is jump over a depression divider within ten seconds. The dog didn't fifty-fifty try to avoid the "aversive stimulus"; it had previously "learned" that nothing it did would reduce the probability of information technology receiving a shock. A follow-upwardly experiment involved three dogs affixed in harnesses, including ane that received shocks of identical intensity and duration to the others, but the lever which would otherwise accept allowed the dog a degree of control was left disconnected and didn't practice anything. The first 2 dogs quickly recovered from the experience, but the third domestic dog suffered chronic symptoms of clinical depression as a consequence of this perceived helplessness.

A further series of experiments showed that, similar to humans, under conditions of long-term intense psychological stress, effectually one third of dogs exercise not develop learned helplessness or long-term depression.[69] [seventy] Instead these animals somehow managed to find a mode to handle the unpleasant state of affairs in spite of their by experience. The corresponding characteristic in humans has been found to correlate highly with an explanatory style and optimistic attitude that views the state of affairs as other than personal, pervasive, or permanent.

Since these studies, symptoms analogous to clinical depression, neurosis, and other psychological conditions have also been accepted as being inside the scope of emotion in domestic dogs. The postures of dogs may indicate their emotional land.[71] [72] In some instances, the recognition of specific postures and behaviors tin be learned.[73]

Psychology research has shown that when humans gaze at the face up of another human, the gaze is not symmetrical; the gaze instinctively moves to the correct side of the face to obtain data virtually their emotions and state. Research at the Academy of Lincoln shows that dogs share this instinct when coming together a human, and only when coming together a human being (i.eastward. not other animals or other dogs). They are the only non-primate species known to share this instinct.[74] [75]

The beingness and nature of personality traits in dogs have been studied (15,329 dogs of 164 different breeds). Five consequent and stable "narrow traits" were identified, described every bit playfulness, curiosity/fearlessness, chase-proneness, sociability and aggressiveness. A further higher order centrality for shyness–boldness was also identified.[76] [77]

Dogs presented with images of either human or dog faces with different emotional states (happy/playful or angry/aggressive) paired with a single vocalization (voices or barks) from the same individual with either a positive or negative emotional land or chocolate-brown racket. Dogs look longer at the face whose expression is congruent to the emotional land of the phonation, for both other dogs and humans. This is an ability previously known only in humans.[78] The beliefs of a dog tin can non always be an indication of its friendliness. This is because when a dog wags its tail, most people interpret this every bit the dog expressing happiness and friendliness. Though indeed tail wagging can express these positive emotions, tail wagging is as well an indication of fearfulness, insecurity, challenging of dominance, establishing social relationships or a warning that the canis familiaris may bite.[79]

Some researchers are commencement to investigate the question of whether dogs have emotions with the assistance of magnetic resonance imaging.[80]

Elephants [edit]

Elephants are known for their empathy towards members of the same species as well equally their cognitive memory. While this is true scientists continuously debate the extent to which elephants feel emotion. Observations show that elephants, like humans, are concerned with distressed or deceased individuals, and render assistance to the ailing and show a special involvement in expressionless bodies of their own kind,[81] however this view is interpreted past some every bit existence anthropomorphic.[82]

Elephants have recently been suggested to pass mirror self-recognition tests, and such tests have been linked to the capacity for empathy.[83] Nonetheless, the experiment showing such actions did not follow the accepted protocol for tests of self-recognition, and earlier attempts to evidence mirror self-recognition in elephants have failed, so this remains a contentious merits.[ commendation needed ]

Elephants are also deemed to show emotion through vocal expression, specifically the rumble vocalization. Rumbles are frequency modulated, harmonically rich calls with central frequencies in the infrasonic range, with clear formant structure. Elephants exhibit negative emotion and/or increased emotional intensity through their rumbles, based on specific periods of social interaction and agitation.[84]

Cats [edit]

Cat's response to a fear inducing stimulus.

It has been postulated that domestic cats tin learn to dispense their owners through vocalizations that are similar to the cries of homo babies. Some cats learn to add a purr to the vocalisation, which makes it less harmonious and more dissonant to humans, and therefore harder to ignore. Individual cats larn to brand these vocalizations through trial-and-mistake; when a particular vocalization elicits a positive response from a human, the probability increases that the cat volition apply that voice in the future.[85]

Growling can be an expression of badgerer or fear, like to humans. When annoyed or aroused, a cat wriggles and thumps its tail much more vigorously than when in a contented state. In larger felids such as lions, what appears to exist irritating to them varies between individuals. A male person lion may let his cubs play with his mane or tail, or he may hiss and hit them with his paws.[86] Domestic male person cats also accept variable attitudes towards their family members, for case, older male siblings tend not to go near younger or new siblings and may even testify hostility toward them.

Hissing is besides a vocalization associated with either offensive or defensive assailment. They are usually accompanied past a postural display intended to take a visual consequence on the perceived threat. Cats hiss when they are startled, scared, angry, or in pain, and likewise to scare off intruders into their territory. If the hiss and growl warning does non remove the threat, an assault by the true cat may follow. Kittens as immature as two to iii weeks will potentially hiss when first picked up by a human.[87]

Honeybees [edit]

Honeybees become pessimistic after existence shaken

Honeybees ("Apis mellifera carnica") were trained to extend their proboscis to a ii-component odour mixture (CS+) predicting a reward (eastward.g., i.00 or 2.00 M sucrose) and to withhold their proboscis from some other mixture (CS−) predicting either penalisation or a less valuable reward (e.k., 0.01 1000 quinine solution or 0.3 M sucrose). Immediately after training, half of the honeybees were subjected to vigorous shaking for 60 s to simulate the land produced past a predatory assail on a concealed colony. This shaking reduced levels of octopamine, dopamine, and serotonin in the hemolymph of a separate group of honeybees at a time point respective to when the cerebral bias tests were performed. In honeybees, octopamine is the local neurotransmitter that functions during reward learning, whereas dopamine mediates the ability to acquire to associate odours with quinine penalization. If flies are fed serotonin, they are more aggressive; flies depleted of serotonin notwithstanding exhibit assailment, but they do and so much less frequently.

Within v minutes of the shaking, all the trained bees began a sequence of unreinforced exam trials with 5 olfactory property stimuli presented in a random order for each bee: the CS+, the CS−, and three novel odours equanimous of ratios intermediate between the two learned mixtures. Shaken honeybees were more likely to withhold their mouthparts from the CS− and from the nearly similar novel odor. Therefore, agitated honeybees display an increased expectation of bad outcomes like to a vertebrate-similar emotional state. The researchers of the study stated that, "Although our results do not let the states to make whatever claims virtually the presence of negative subjective feelings in honeybees, they phone call into question how nosotros identify emotions in any non-man creature. It is logically inconsistent to claim that the presence of pessimistic cognitive biases should be taken as confirmation that dogs or rats are anxious but to deny the same conclusion in the instance of honeybees."[viii] [88]

Crayfish [edit]

Crayfish naturally explore new environments merely brandish a general preference for dark places. A 2014 study[89] on the freshwater crayfish Procambarus clarkii tested their responses in a fear epitome, the elevated plus maze in which animals choose to walk on an elevated cross which offers both aversive and preferable conditions (in this case, two artillery were lit and ii were dark). Crayfish which experienced an electric stupor displayed enhanced fearfulness or anxiety every bit demonstrated by their preference for the dark arms more than than the light. Furthermore, shocked crayfish had relatively higher brain serotonin concentrations coupled with elevated blood glucose, which indicates a stress response.[ninety] Moreover, the crayfish calmed down when they were injected with the benzodiazepine anxiolytic, chlordiazepoxide, used to treat anxiety in humans, and they entered the dark as normal. The authors of the written report concluded "...stress-induced abstention behavior in crayfish exhibits striking homologies with vertebrate anxiety."

A follow-up study using the aforementioned species confirmed the anxiolytic issue of chlordiazepoxide, but moreover, the intensity of the anxiety-like behaviour was dependent on the intensity of the electrical shock until reaching a plateau. Such a quantitative relationship betwixt stress and anxiety is also a very mutual feature of man and vertebrate anxiety.[91]

Run across also [edit]

- Altruism in animals

- Beast cognition

- Animate being advice

- Creature consciousness

- Animal faith

- Animal sexual behaviour § Sex for pleasure

- Empathy § In animals

- Evolution of emotion

- Fear § In animals

- Monkey painting

- Neuroethology

- Pain in animals

- Advantage system § Animals vs. humans

- Self-awareness § In animals

- Thomas Nagel (seminal paper, "What is it like to be a bat?")

References [edit]

- ^ a b Cabanac, Michel (2002). "What is emotion?". Behavioural Processes. 60 (2): 69–83. doi:ten.1016/S0376-6357(02)00078-v. PMID 12426062. S2CID 24365776.

- ^ Panksepp, J. (1982). "Toward a general psychobiological theory of emotions". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 5 (three): 407–422. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00012759. S2CID 145746882.

- ^ "Emotions help animals to make choices (press release)". University of Bristol. 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Jacky Turner; Joyce D'Silva, eds. (2006). Animals, Ethics and Trade: The Challenge of Brute Sentience. Earthscan. ISBN9781844072545 . Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Wong, M. (2013). "How to identify grief in animals". Scientific American. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Rygula, R; Pluta, H; P, Popik (2012). "laughing rats are optimistic". PLOS One. 7 (12): e51959. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...751959R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051959. PMC3530570. PMID 23300582.

- ^ Douglas, C.; Bateson, M.last2=Bateson; Walsh, C.; Béduéc, A.; Edwards, S.A. (2012). "Ecology enrichment induces optimistic cognitive biases in pigs". Practical Animal Behaviour Science. 139 (one–2): 65–73. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2012.02.018.

- ^ a b Bateson, M.; Desire, South.; Gartside, S.E.; Wright, G.A. (2011). "Agitated honeybees exhibit pessimistic cognitive biases". Current Biology. 21 (12): 1070–1073. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.017. PMC3158593. PMID 21636277.

- ^ a b c d eastward f Panksepp, Jaak (2005). "Affective consciousness: Core emotional feelings in animals and humans". Consciousness and Knowledge. 14 (1): xxx–80. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2004.10.004. PMID 15766890. S2CID 8416255.

- ^ Merriam-Webster (2004). The Merriam-Webster dictionary (11th ed.). Springfield, MA: Author.

- ^ Fox, E. (2008). Emotion Scientific discipline: An Integration of Cognitive and Neuroscientific Approaches. Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 16–17. ISBN978-0-230-00517-4.

- ^ Ekman, P. (1992). "An argument for basic emotions". Cognition and Emotion. 6 (3): 169–200. CiteSeerX10.1.1.454.1984. doi:10.1080/02699939208411068.

- ^ Barnard, S.; Matthews, 50.; Messori, S.; Podaliri-Vulpiani, M.; Ferri, Northward. (2015). "Laterality equally an indicator of emotional stress in ewes and lambs during a separation test". Animal Noesis. 19 (1): one–8. doi:10.1007/s10071-015-0928-3. PMID 26433604. S2CID 7008274.

- ^ Handel, S. (2011-05-24). "Classification of Emotions". Retrieved 30 Apr 2012.

- ^ a b c d Dawkins, Chiliad. (2000). "Animal minds and beast emotions". American Zoologist. 40 (6): 883–888. CiteSeerX10.i.1.596.3220. doi:10.1668/0003-1569(2000)040[0883:amaae]2.0.co;2. [ permanent expressionless link ]

- ^ a b Watson, J. B. (1930). Behaviorism (Revised Ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 11.

- ^ Dixon, B. (2001). "Animal emotions". Ethics and the Surroundings. half-dozen (2): 22–xxx. doi:10.2979/ete.2001.6.2.22.

- ^ Moussaieff Masson, J.; McCarthy, South. (1996). When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals. Delta. ISBN978-0-385-31428-two.

- ^ D.S. Mills; J.N. Marchant-Forde, eds. (2010). The Encyclopedia of Applied Animal Behaviour and Welfare . CABI. ISBN978-0851997247.

- ^ Morgan, C.50. (1903). An Introduction to Comparative Psychology (2nd ed.). West. Scott, London. pp. 59.

- ^ a b Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression Of The Emotions In Human being And Animals. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- ^ Hess, U. and Thibault, P., (2009). Darwin and emotion expression. American Psychological Clan, 64(two): 120-128.[1]

- ^ Scruton, R; Tyler, A. (2001). "Argue: Do animals accept rights?". The Ecologist. 31 (2): 20–23. ProQuest 234917337.

- ^ Oately, Yard.; Jenkins, J.M. (1996). Understanding Emotions. Blackwell Publishers. Malden, MA. ISBN978-1-55786-495-6.

- ^ a b Paul, E; Harding, East; Mendl, Thousand (2005). "Measuring emotional processes in animals: the utility of a cognitive approach". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 29 (3): 469–491. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.01.002. PMID 15820551. S2CID 14127825.

- ^ Haselton, M. Yard.; Nettle, D. & Andrews, P. W. (2005). The evolution of cognitive bias. In D. One thousand. Buss (Ed.), The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology: Hoboken, NJ, United states of america: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 724–746.

- ^ Anoint, H.; Fiedler, K. & Strack, F. (2004). Social knowledge: How individuals construct social reality. Hove and New York: Psychology Press. p. 2.

- ^ Harding, EJ; Paul, ES; Mendl, M (2004). "Animal behaviour: cognitive bias and affective state". Nature. 427 (6972): 312. Bibcode:2004Natur.427..312H. doi:x.1038/427312a. PMID 14737158. S2CID 4411418.

- ^ Malhi, Gin S; Baune, Berhard T; Porter, Richard J (December 2015). "Re-Cognizing mood disorders". Bipolar Disorders. 17: 1–2. doi:x.1111/bdi.12354. ISSN 1398-5647. PMID 26688286.

- ^ Sherwin, C.M.; Olsson, I.A.South. (2004). "Housing conditions affect self-administration of anxiolytic past laboratory mice". Animate being Welfare. 13: 33–38.

- ^ Fajardo, C.; et al. (4 March 2008). "Von Economo neurons are present in the dorsolateral (dysgranular) prefrontal cortex of humans". Neuroscience Letters. 435 (iii): 215–218. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.048. PMID 18355958. S2CID 8454354.

- ^ a b c d Hof, P.R.; Van Der Gucht, E. (2007). "Structure of the cognitive cortex of the humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae (Cetacea, Mysticeti, Balaenopteridae)". Anatomical Record Part A. 290 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1002/ar.20407. PMID 17441195. S2CID 15460266.

- ^ Coghlan, A. (27 November 2006). "Whales boast the brain cells that 'make us man'". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 27 Baronial 2017.

- ^ Butti, C; Sherwood, CC; Hakeem, AY; Allman, JM; Hof, PR (July 2009). "Full number and volume of Von Economo neurons in the cognitive cortex of cetaceans". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 515 (2): 243–59. doi:ten.1002/cne.22055. PMID 19412956. S2CID 6876656.

- ^ Hakeem, A. Y.; Sherwood, C. C.; Bonar, C. J.; Butti, C.; Hof, P. R.; Allman, J. M. (2009). "Von Economo neurons in the elephant brain". The Anatomical Record. 292 (2): 242–eight. doi:10.1002/ar.20829. PMID 19089889. S2CID 12131241.

- ^ Panksepp, J; Burgdorf, J (2003). ""Laughing" rats and the evolutionary antecedents of human being joy?". Physiology and Behavior. 79 (3): 533–547. CiteSeerX10.1.i.326.9267. doi:ten.1016/s0031-9384(03)00159-8. PMID 12954448. S2CID 14063615.

- ^ Knutson, B; Burgdorf, J; Panksepp, J (2002). "Ultrasonic vocalizations as indices of affective states in rats" (PDF). Psychological Message. 128 (six): 961–977. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.half dozen.961. PMID 12405139. S2CID 4660938. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-28.

- ^ Panksepp, J; Burgdorf, J (2000). "fifty-kHz chirping (laughter?) in response to conditioned and unconditioned tickle-induced reward in rats: effects of social housing and genetic variables". Behavioural Brain Research. 115 (1): 25–38. doi:x.1016/s0166-4328(00)00238-2. PMID 10996405. S2CID 29323849.

- ^ a b Boissy, A.; et al. (2007). "Cess of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare". Physiology & Behavior. 92 (3): 375–397. doi:x.1016/j.physbeh.2007.02.003. PMID 17428510. S2CID 10730923.

- ^ Elfenbein, H.A.; Ambady, N. (2002). "On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis". Psychological Message. 128 (two): 203–235. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.two.203. PMID 11931516. S2CID 16073381.

- ^ Winford, J.Northward. (2007). "Almost human, and sometimes smarter". New York Times . Retrieved Oct 26, 2013.

- ^ "Mama gorilla won't let go of her dead infant". Associated Press. 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Bekoff, Marc (2007). The Emotional Lives of Animals: A Leading Scientist Explores Animal Joy, Sorrow, and Empathy--and why They Matter. New World Library. ISBN9781577315025.

- ^ McGraw, C. (1985). "Gorilla's Pets: Koko Mourns Kittens Expiry". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Wechkin, Southward.; Masserman, J.H.; Terris, Due west. (1964). "Stupor to a conspecific equally an aversive stimulus". Psychonomic Science. one (1–12): 47–48. doi:10.3758/bf03342783.

- ^ Masserman, J.; Wechkin, M.S.; Terris, W. (1964). "Donating behavior in rhesus monkeys". American Journal of Psychiatry. 121 (6): 584–585. CiteSeerX10.i.1.691.4969. doi:10.1176/ajp.121.half dozen.584. PMID 14239459.

- ^ De Waal, F.B.G. & Aureli, F. (1996). Consolation, reconciliation, and a possible cognitive difference between macaques and chimpanzees. In A.Eastward. Russon, Thou.A. Bard, and S.T. Parker (Eds.), Reaching Into Thought: The Minds Of The Bang-up Apes (pp. fourscore-110). Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing.

- ^ Watts, D.P., Colmenares, F., & Arnold, K. (2000). Redirection, consolation, and male person policing: How targets of aggression interact with bystanders. In F. Aureli and F.B.One thousand. de Waal (Eds.), Natural Conflict Resolution (pp. 281-301). Berkeley: University of California Printing.

- ^ Parr, L.A. (2001). "Cognitive and physiological markers of emotional awareness in chimpanzees". Animal Noesis. 4 (3–iv): 223–229. doi:ten.1007/s100710100085. PMID 24777512. S2CID 28270455.

- ^ Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective. Neuroscience: The Foundation of Homo and Animal Emotions. Oxford University Press, New York. p. 480.

- ^ Panksepp, J.B.; Lahvis, M.P. (2011). "Rodent empathy and affective neuroscience". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 35 (ix): 1864–1875. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.05.013. PMC3183383. PMID 21672550.

- ^ Rice, Grand.East.; Gainer, P (1962). "Altruism in the albino rat". Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 55: 123–125. doi:10.1037/h0042276. PMID 14491896.

- ^ Mirsky, I.A.; Miller, R.E.; Murphy, J.B. (1958). "The communication of bear upon in rhesus monkeys I. An experimental method". Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 6 (3): 433–441. doi:10.1177/000306515800600303. PMID 13575267. S2CID 2646373.

- ^ Langford, D.J.; Crager, S.East.; Shehzad, Z.; Smith, S.B.; Sotocinal, S.Grand.; Levenstadt, J.S.; Mogil, J.South. (2006). "Social modulation of pain as evidence for empathy in mice". Science (Submitted manuscript). 312 (5782): 1967–1970. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1967L. doi:10.1126/science.1128322. PMID 16809545. S2CID 26027821.

- ^ Reimerta, I.; Bolhuis, J.Due east; Kemp, B.; Rodenburg., T.B. (2013). "Indicators of positive and negative emotions and emotional contagion in pigs". Physiology and Behavior. 109: 42–50. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.11.002. PMID 23159725. S2CID 29192088.

- ^ Atsak, P.; Ore, M; Bakker, P.; Cerliani, L.; Roozendaal, B.; Gazzola, V.; Moita, Grand.; Keysers, C. (2011). "Feel modulates vicarious freezing in rats: a model for empathy". PLOS ONE. six (7): e21855. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621855A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021855. PMC3135600. PMID 21765921.

- ^ Kavaliers, M.; Colwell, D.D.; Choleris, E. (2003). "Learning to fear and cope with a natural stressor: individually and socially caused corticosterone and abstention responses to biting flies". Hormones and Behavior. 43 (1): 99–107. doi:10.1016/s0018-506x(02)00021-1. PMID 12614639. S2CID 24961207.

- ^ Kim, Eastward.J.; Kim, E.S.; Covey, E.; Kim, J.J. (2010). "Social manual of fear in rats: the office of 22-kHz ultrasonic distress vocalisation". PLOS I. 5 (12): e15077. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515077K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015077. PMC2995742. PMID 21152023.

- ^ Bruchey, A.One thousand.; Jones, C.E.; Monfils, Chiliad.H. (2010). "Fear conditioning past-proxy: social manual of fearfulness during memory retrieval". Behavioural Brain Research. 214 (1): fourscore–84. doi:x.1016/j.bbr.2010.04.047. PMC2975564. PMID 20441779.

- ^ Jeon, D.; Kim, S.; Chetana, One thousand.; Jo, D.; Ruley, H.E.; Lin, S.Y.; Shin, H.S.; Kinet, Jean-Pierre; Shin, Hee-Sup (2010). "Observational fear learning involves affective hurting organisation and Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels in ACC". Nature Neuroscience. 13 (4): 482–488. doi:10.1038/nn.2504. PMC2958925. PMID 20190743.

- ^ Chen, Q.; Panksepp, J.B.; Lahvis, G.P. (2009). "Empathy is moderated by genetic groundwork in mice". PLOS ONE. 4 (two): e4387. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4387C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004387. PMC2633046. PMID 19209221.

- ^ Smith, A.V.; Proops, L.; Grounds, K.; Wathan, J.; McComb, K. (2016). "Functionally relevant responses to human facial expressions of emotion in the domestic horse (Equus caballus)". Biology Letters. 12 (ii): 20150907. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0907. PMC4780548. PMID 26864784.

- ^ Bekoff, Marc (2007). The Emotional Lives of Animals . Novato, California: New Globe Library. p. 1.

- ^ Orlaith, Due north.F.; Bugnyar, T. (2010). "Do Ravens Bear witness Consolation? Responses to Distressed Others". PLOS I. 5 (5): e10605. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...510605F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010605. PMC2868892. PMID 20485685.

- ^ Edgar, J.50.; Paul, E.S.; Nicol, C.J. (2013). "Protective mother hens: Cognitive influences on the avian maternal response". Animate being Behaviour. 86 (ii): 223–229. doi:x.1016/j.anbehav.2013.05.004. ISSN 0003-3472. S2CID 53179718.

- ^ Edgar, J.50.; Lowe, J.C.; Paul, E.S.; Nicol, C.J. (2011). "Avian maternal response to chick distress". Proceedings of the Imperial Club B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1721): 3129–3134. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2701. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC3158930. PMID 21389025.

- ^ Broom, D.1000.; Fraser, A.F. (2015). Domestic Animal Behaviour and Welfare (5 ed.). CABI Publishers. pp. 42, 53, 188. ISBN978-1780645391.

- ^ Edgar, J.Fifty.; Paul, E.S.; Harris, L.; Penturn, Southward.; Nicol, C.J. (2012). "No evidence for emotional empathy in chickens observing familiar adult conspecifics". PLOS I. 7 (ii): e31542. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731542E. doi:x.1371/journal.pone.0031542. PMC3278448. PMID 22348100.

- ^ Seligman, Grand. E. (1972). Learned helplessness. Almanac Review of Medicine, 207-412.

- ^ Seligman, Yard. E.; Groves, D. P. (1970). "Nontransient learned helplessness". Psychonomic Science. 19 (three): 191–192. doi:10.3758/BF03335546.

- ^ "How to Avert a Canis familiaris Bite -Be polite and pay attention to trunk language". The Humane Club of the United States. 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- ^ "Canis familiaris bite prevention & canine torso linguistic communication" (PDF). San Diego Humane Guild. Archived from the original (PDF) on Baronial 6, 2017. Retrieved April xxx, 2017.

- ^ "New Pecker In California to Protect Dogs in Constabulary Altercations - PetGuide". PetGuide. 2017-02-22. Retrieved 2017-06-22 .

- ^ Guo, Thousand.; Hall, C.; Hall, S.; Meints, M.; Mills, D. (2007). "Left gaze bias in homo infants, rhesus monkeys, and domestic dogs". Perception. 3. Archived from the original on 2011-07-xv. Retrieved 2010-06-24 .

- ^ Alleyne, R. (2008-10-29). "Dogs tin can read emotion in man faces". Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2011-01-11. Retrieved 2010-06-24 .

- ^ Svartberg, Thousand.; Tapper, I.; Temrin, H.; Radesäter, T.; Thorman, S. (2004). "Consistency of personality traits in dogs". Fauna Behaviour. 69 (2): 283–291. doi:x.1016/j.anbehav.2004.04.011. S2CID 53154729.

- ^ Svartberga, 1000.; Forkman, B. (2002). "Personality traits in the domestic canis familiaris (Canis familiaris)" (PDF). Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 79 (2): 133–155. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00121-1.

- ^ Albuquerque, Northward.; Guo, K.; Wilkinson, A.; Savalli, C.; Otta, E.; Mills, D. (2016). "Dogs recognize domestic dog and human emotions". Biology Messages. 12 (1): 20150883. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0883. PMC4785927. PMID 26763220.

- ^ Coren, Stanley (Dec v, 2011). "What a Wagging Dog Tail Really Means: New Scientific Data Specific tail wags provide data about the emotional state of dogs". Psychology Today. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ Berns, G. S.; Brooks, A. Chiliad.; Spivak, M. (2012). "Functional MRI in Awake Unrestrained Dogs". PLOS 1. vii (5): e38027. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738027B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038027. PMC3350478. PMID 22606363.

- ^ Douglas-Hamilton, Iain; Bhalla, Shivani; Wittemyer, George; Vollrath, Fritz (2006). "Behavioural reactions of elephants towards a dying and deceased matriarch". Applied Animal Behaviour Scientific discipline. 100 (1–2): 87–102. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2006.04.014. ISSN 0168-1591.

- ^ Plotnik, Joshua M.; Waal, Frans B. 1000. de (2014-02-eighteen). "Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) reassure others in distress". PeerJ. 2: e278. doi:x.7717/peerj.278. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC3932735. PMID 24688856.

- ^ Bates, L, A. (2008). "Practice Elephants Show Empathy?". Periodical of Consciousness Studies. fifteen: 204–225.

- ^ Altenmüller, Eckart; Schmidt, Sabine; Zimmermann, Elke (2013). Evolution of emotional communication from sounds in nonhuman mammals to speech communication and music in homo. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-174748-ix. OCLC 940556012.

- ^ "Cats do command humans, report finds". LiveScience.com. 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-20 .

- ^ King of beasts#cite ref-105

- ^ Wikipedia, Source. (2013). True cat behavior : cats and humans, true cat communication, cat intelligence, cat pheromone, cat. University-Press Org. ISBN978-ane-230-50106-2. OCLC 923780361.

- ^ Gorvett, Zaria (2021-xi-29). "Why insects are more sensitive than they seem". BBC Future . Retrieved 2022-01-03 .

- ^ Fossat, P.; Bacqué-Cazenave, J.; De Deurwaerdère, P.; Delbecque, J.-P.; Cattaert, D. (2014). "Anxiety-like behavior in crayfish is controlled past serotonin". Scientific discipline. 344 (6189): 1293–1297. Bibcode:2014Sci...344.1293F. doi:10.1126/science.1248811. PMID 24926022. S2CID 43094402.

- ^ Sneddon, Fifty.U. (2015). "Pain in aquatic animals". Journal of Experimental Biological science. 218 (7): 967–976. doi:10.1242/jeb.088823. PMID 25833131.

- ^ Fossat, P.; Bacqué-Cazenave, J.; De Deurwaerdère, P.; Cattaert, D.; Delbecque, J.P. (2015). "Serotonin, but not dopamine, controls the stress response and anxiety-like behavior in the crayfish Procambarus clarkii". Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (17): 2745–2752. doi:10.1242/jeb.120550. PMID 26139659.

Further reading [edit]

- Bekoff, M.; Jane Goodall (2007). The Emotional Lives of Animals. ISBN978-one-57731-502-5.

- Holland, J. (2011). Unlikely Friendships: 50 Remarkable Stories from the Animal Kingdom.

- Swirski, P. (2011). "Yous'll Never Make a Monkey Out of Me or Altruism, Proverbial Wisdom, and Bernard Malamud'southward God's Grace." American Utopia and Social Engineering in Literature, Social Thought, and Political History. New York, Routledge.

- Mendl, M.; Burman, O.H.P.; Paul, E.S. (2010). "An integrative and functional framework for the written report of animal emotion and mood". Proceedings of the Imperial Society B. 277 (1696): 2895–2904. doi:x.1098/rspb.2010.0303. PMC2982018. PMID 20685706.

- Anderson, D. J.; Adolphs, R. (2014). "A framework for studying emotions across species". Jail cell. 157 (1): 187–200. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.003. PMC4098837. PMID 24679535.

- Wohlleben, Peter (2017-11-07). The Inner Life of Animals: Love, Grief, and Compassion — Surprising Observations of a Hidden World. Translated past Jane Billinghurst. Greystone Books Ltd. ISBN9781771643023. Foreword by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson. Get-go published in 2016 in German, under the title Das Seelenleben der Tiere.

- "Sensitivity of pigs and the thieving of squirrels — all part of animals' inner lives". The Washington Mail service. 2017-12-08.

- Safina, Carl (2015). Beyond Words What Animals Think and Feel. Henry Holt & Company Inc. ISBN978-0805098884.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emotion_in_animals

Posted by: redmondthentent.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Do Animals Help Humans With Emotional Support"

Post a Comment